From now on The Trip gets a little truncated. I have never been good at maths but I know that six into four won’t go. Some divergence from canon is necessary. So today began at Bashall Eaves …

Source: Cartmel and Greta Hall

From now on The Trip gets a little truncated. I have never been good at maths but I know that six into four won’t go. Some divergence from canon is necessary. So today began at Bashall Eaves …

Source: Cartmel and Greta Hall

With the best intentions of leaving at 40 minutes earlier, it will come of no surprise to any who know us well that we pulled away at 9.10am. Slipping with remarkable ease through the Surrey rush h…

Source: The Inn at Whitewell

It’s not just me that writes stuff about me. Here’s my twin brother writing about something properly interesting that we’re doing next week.

I suppose the idea began the first time I saw The Trip, inasmuch as it started from an idle thought along the lines of “I’d like to do that one day”. The first time I saw it was on its first airing in the UK, on BBC2, back in the autumn of 2010. Life was different then. Two years before I had my first child, four years before my second. Another series has taken Steve and Rob to Italy (2014) and, as I write, they are on location filming the third series in northern Spain.

From time to time it came back to me. The movie version on a transatlantic plane in 2011. The second series broadcast in Spring 2014. Passing mentions in interviews, podcasts and articles. A Children In Need sketch. A lingering memory of a particular impression that cried out to be retold or shared on…

View original post 1,061 more words

Make the most of the downhills in your investment strategy (Alexis Martín, Flickr)

Analogies can be hit and miss, but that doesn’t stop me from deploying them almost constantly in conversation. Because running is such a significant part of my life, there has been a tendency to see much of the work I do through the lens of physical activity and effort proves to be highly relatable in many service journeys.

Thanks to my one-time boss and good friend Darren, I was engaged in a conversation on Facebook recently pertaining to investments. With an undulating landscape of financial predictions, the chat was about how your unsophisticated public investor might make the right decisions about how much to invest and when.

Darren highlighted the strategy of Pound Cost Averaging, something I wasn’t aware of and which can be described thusly

The basic idea behind pound-cost averaging is straightforward; the term simply refers to investing money in equal amounts at regular intervals. One way to do this is with a lump sum that you’d prefer to invest gradually–for example, by taking £1,000 and investing £100 each month for 10 months. Or you can pound-cost average on an open-ended basis by investing, say, £100 out of your paycheque every month. The latter is the most common method; in fact, if you have a defined contribution pension plan, you’ve probably already been pound-cost averaging in this way.

Source: Morningstar

Now, that’s one way of essentially distributing an investment over time to spread the risk, prevent you getting carried away trying to read the market but keeping you ‘in the zone’ of investing when you might not feel like it.

Aside

There’s good evidence that it’s a very sensible strategy, albeit one that is not at the aggressive end of possible returns. Writing with refreshing candour in The Spectator in November 2015 Louise Cooper highlighted how such a simple approach is a solid antidote to the lack of expertise that Fund Managers really have.

Now, what I’d like to see – and what interested me about Darren’s comments – was the potential to flex these regular contributions in line with the market’s movements. This is where the analogy really begins.

As a long-distance runner, the absolute best thing you can learn in an event like the marathon is pacing. You want to distribute the effort across the race and there’s some really good literature to support it. No course is completely flat and this means you have to modify the effort to match the gradient, you ease off a bit on the uphill and, within reason, make some benefit on the downhills. Using Heart Rate as a guide you might aim for a consistent effort of 165 BPM, keeping that constant on hills means dropping pace, on the downhills your heart is under less load so you can speed up a bit. Recently the website Flying Runner allowed you to create a minute-per-mile pace band that reflected the slight modifications you’d make throughout the race depending on the gradient or effort required.

Now consider investing, let’s say you want to invest £10,000 this year. You can trickle that out evenly across the year in £833.33 increments, assuming a flat market. But what if you wanted to follow the FTSE and say invest a little more when the market is on a downturn and invest a little less when it’s climbing? Doing so would make the most of the market movement but keep you within a framework that spreads the load.

There are issues with this approach of course: a period of consistent decline might over-stretch a finite investment pot, so if I put £850 in for the first 4 months of the year then I’ve used up more of my £10,000 but with no guarantee that I’ll make it up if the market doesn’t subsequently ascend. That’s a crucial difference. In the marathon, we know the profile and the distance of the course in advance and can plan how much to scrub off or add on to our pace with the gradients and the total distance predetermined. That said, this is a longer play than a marathon and a decade of investing this way is sure to see the amounts even out. The problem then becomes setting a monthly amount that you can afford: For example setting hard maximum investment and a hard minimum that is reviewed each year according to salary changes.

The second issue is fees and logistics. The sad truth is that nobody appears to be setup to allow the public to effortlessly invest in this manner. Often each investment incurs a commission thereby wiping out the gains if you’re making 12 of them per year. Additionally, no provider appears to offer automatic modifications that track the market gradient against your personal tolerances [happy to be corrected], although Share Centre certainly support a savvy customer doing it themselves. Evidently, there’s nothing to stop one doing it oneself with a spreadsheet and a diligent approach to calling in or going online to tweak the figures. Does this constitute a direct example of where Big Finance is theoretically working against customer behaviour by penalising us through regulatory-inflicted charges? Is it an example of an opportunity that could be exploited by FinTech, able to quickly build a front-end to an investment vehicle that is aligned to plausible customer behaviour? Well, until I can find a service to meet my desired approach I’ll just have to work on my own Google Spreadsheet and work towards the release of the first endurance-inspired investment strategy. Given that the Brexit marathon starting pistol has just been fired, perhaps now is the time to, caveat emptor, give it a go?

In the world of customer experience, there are certain topics and industry sectors which, if you’re looking for examples of terrible customer service, are like shooting fish in a barrel. Consider, for example, the courier company.

It’s not a trivial thing, every single graph one finds when searching for online shopping shows a precipitous upward curve. We’re all doing it and as a fundamental part of our relationship with brands, it’s a curious thing that something so critical to the customer journey is outsourced to external companies – often at the lowest possible price.

The trouble is, it’s so often the point of the user experience that is most broken. eCommerce retailers have woken up and begun to spend big sums on the optimisation of their digital interaction design. They’re talking choice architecture, multi-variate testing, ethnography, eye-tracking and so on and so on. All very noble, but once we’ve slipped down their wide-necked and increasingly-greasy conversion funnel we’re left at the mercy of the cowboys they have contracted to send us our products.

Many of us are now experiencing that sinking feeling when the confirmation email drops into our box and proudly announces that [insert courier company here] are going to be delivering the purchase. Today on Twitter the comedian Richard Herring began tweeting his experiences of Yodel’s service. It opened a rich vein of commentary on the company’s undeniably appalling fulfilment of orders. Amongst the numerous comical and fantastical examples of their failures, a few posts stood out [ Why I’m boycotting Yodel and Yodel are an incompetent shower ]. It’s quite apparent that customers are now sufficiently motivated by the toxicity of their previous experiences with companies like Yodel, to take this out on the original vendor/provider.

From Terence Eden

Well, the solution’s simple – from now on I don’t accept deliveries from Yodel.

If I buy something and I receive a Yodel tracking ID, I’m cancelling the order.

If a Yodel driver turns up, I’ll refuse to accept delivery.In short, I am firing them – and I suggest you do the same.

In simple terms, customers will actually refuse to purchase from you if they know you’re using a courier who has failed them in the past.

This attribution of responsibility, the guilt by association or the sheer unwillingness to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous delivery companies, anecdotally at least, is an opportunity for eTailers. Consider the benefit of giving customers the confidence that their shipping fee will be going to a highly-rated and ultra-low-failure-rate delivery company? Imagine that your customer can have complete confidence – underwritten by you as vendor – that their parcel will arrive safely, in good time.

If we as experience-obsessed strategists, are mapping and considering the service from end to end, we must insist that significant time and attention is paid to all touch points, including those that businesses choose to outsource (for perfectly legitimate reasons) and that the same care and attention to exceptional user experience is applied to those moments. The critical moment of delivery is too valuable to leave to the cold moneyed hand of procurement decision makers writing contracts with universally-derided delivery partners.

And, if you’re a courier company, perhaps using your twitter feed to merrily announce competition winners while disgruntled customers pick up the pieces (often literally) of your failed service, might not be the most sensible strategy…

UPDATE: After an atrocious delivery experience from ELC/Mothercare I have decided to produce a table showing retailers that use Yodel for their service to avoid them on that basis (other tables exist on MSE and Mumsnet but are out of date)

Mothercare & Early Learning Centre (July 2016) – Will no longer use at-home delivery

Great Little Trading Company – (July 2016) – Will no longer use whilst they contract Yodel

With the Asics Stockholm Marathon just a few weeks away it’s time to take stock of a few things in my running year.

Although not documented on this blog, I’ve set myself a challenge of running every single day this year (at least 3.2k – two miles in old money). This was loosely inspired by Advent Running and the Tracksmith poster, but the origins are neither here nor there. So far I’ve hit it.

Doing a challenge like that has naturally impacted my traditional marathon build-up. I’ve followed a Garmin plan this time around and on rest days I’ve just done light runs but other than that I’ve tried to stick to tempo or threshold training on the selected session days. The big ‘but’ of all this has been the effect it’s had on my overall quality of session: tempo runs are often on tired legs, intervals are not even harder to complete and the long runs in recent weeks have seen some incredibly slow pace and high heart rates.

To make sense of this, or at least allow me to predict what this might all mean for Stockholm I have been fretting about the long runs in particular. In recent weeks, I’ve hit 32.1, 35, 31.1, 33.6 km each weekend. I’ve done 5 runs over 30k this year and a further 5 over 20k. All of which is much more than I’ve done in the past but I’ve been intentionally running them slower. I’ve tried to stick to Zone 2 Heart Rates, under 140bpm which means around 5:10-5:40 pace per km. It should feel easy but after a while it does fatigue you regardless and it begins to hurt as I run more heavily by slumping into slower cadences and mentally I struggle with the discipline of keeping the HR low especially now the days are 15-20 degrees warmer than those first runs of the year.

Today I stumbled across the Tanda discussions from Christof Schwiening‘s blog which I found via Charlie Wartnaby and the sub 3hr Facebook Group. I printed out this graph and started to plot my weekly distance against average pace to see where I sit. Fortunately, Strava’s log page gives me the weekly duration and distance figures so I did a few calculations on bane.info and plotted 12 weeks’ worth of data. To my amazement it had me sitting along the 3hr 15′ contour and, given the strength of this model, I’m quite encouraged by that.

Black x marks indicate my training weeks

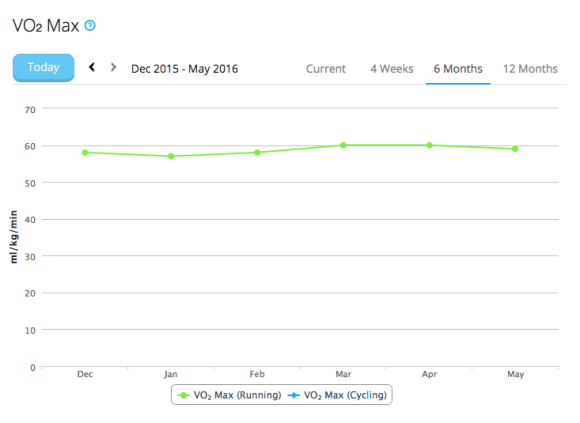

There’s no question that the long runs have really frustrated me, on the days I’ve run slow I’ve wondered how I could even run at paces I was comfortable at in 2015, 2012 and 2011 for the full distance. But then this year I’ve also hit a parkrun PB of 19:03 and regularly go sub 3:45 on my commute runs and in interval sessions. My Garmin VO2 max has been as high as 60 and is currently hovering at 58/59. So I’m fit and, touch-wood, largely injury free. A niggling sciatic nerve, a bit of gluteus numbness and some hints of ITB all might flare up on the day but equally, could not, and if they don’t? Well, to hit 3:15 would be a dream and put me firmly on the road of my 5-year plan to sub 3 with a good opportunity to go quicker in York in October. However, that means averaging 4′ 37″ /km for the entire race and that is a pace which I exceeded for just 25 minutes on Sunday (after 2 hrs 20 mins of slower running). Even with adrenaline and a lighter few weeks ahead I’m not sure I’ve got that in me, and that in itself is a revelation: physiologically the data says I should be able to do it, but my own sense of perceived effort says it’s not.

I’ve got time to set that goal, create the pace band and work out what I’ll go at. Keeping an eye on the temperature (average 18 C) and wind on the day will have a bearing but when you’ve spent a fair amount of coin flying out there, hotels and food, do you really want to risk having 4 hours of hell on the road because you took a risk and went out at a punchy pace?

On the 4th June, we’ll know…

It’s well understood that the country is facing an obesity epidemic. There are few topics in public health as well covered in recent years. The sugar tax is happening and much debate is underway about the role governments and responsible bodies should have in modifying our irrational and damaging behaviour.

I have a vested interest in the subject from several perspectives: As a concerned citizen, as an endurance runner, as a proud supporter of the UK’s biggest mass exercise movement in parkrun and as a behavioural psychologist working in persuasive consumer design.

My empirical background adds a healthy dose of cynicism when I read today that the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) suggest the use of exercise labels for food to replace or augment the nutrition labelling.

The reason this is being suggested is that nutrition labelling isn’t working. The arguments here concern the fact that the detail is too complex for the general public, that it causes an unhealthy focus on calorie content that there is considerable ambiguity on how this information should be used by the consumer and the presentation of portion sizes.

I contend that the solution proposed by RSPH is also doomed to failure because it doesn’t affect the decision at the point of sale and allows our inner defence lawyer to contend and justify the purchase because ‘i’ll deal with the consequences of this bad choice later with some exercise’. It’s the same reason that carbon offsetting is an acceptance that we make the wrong choice with travel. This is what behavioural economists call the default norm, we are not affecting the ingrained status quo of the bad choice. It’s better than nothing, perhaps, but it avoids dealing with the real problem – which is that we don’t promote real nutritious and healthy food anywhere near enough.

To explain why this was felt to be a worthwhile intervention, some well-meaning commentators and the RSPH have pointed to a study in Baltimore, widely reported in October 2014 [CNN, Washington Post], and published in the American Journal of Public Health. This study placed 20 cm x 28 cm signs in a point of sale (PoS) display in stores that drew attention to the amount of exercise required to ‘burn off’ the carbonated drinks in the adjacent cabinet. It worked, and less drink was sold. However, there are a handful of reasons we cannot extrapolate the findings from this to the RSPH proposition.

The people that read labels and packaging tend toward higher levels of education and are already motivated by a health goal: fat loss, protein intake etc. so the people making use of labels to change behaviour are already past the trigger point. RSPH cite Dr. Hamlin’s paper about the attention given to front of pack (FOP) labelling but even this paper acknowledges the profound limitations of FOP in the context of the myriad of marketing pressure applied to the persuasion for sale. They also acknowledge [Cowburn, G., Stockley, L., 2005] that the interpretation of labelling is going to be challenged by levels of education and nutritional sophistication. Finally, although the RSPH present research that indicates people would be ‘three times more likely to indicate they would undertake physical activity’, there is no evidence this intent is or would be followed-through.

Solutions may be found by modifying packaging and one could argue that it’s just part of a broad approach to changing perception and behaviour but I contend that it’s actually damaging to press ahead with it. To spend time considering and executing this is to distract from the real solution which is to make healthy food choices the norm. Considerable time and effort must be expended in the persuasive design industry to work with our natural biases and present good food as the obvious, natural and common choice. To dilute the salience of bad food in preference for clean, natural unprocessed alternatives.

I look forward to Public Health sector that recognises that until we confront the universally damaging food we sell in the same way we’ve confronted tobacco (i.e. through demonisation), we’re not going to be able to educate people away from their irrational desire to pursue the forbidden fruit. We cannot go around treating exercise, worthy and valuable as it is, as the cure for a problem we’ve not had the guts to deal with at source. You wouldn’t promote chemotherapy on cigarette packets … would you?

The RSPH paper itself acknowledges that the solution needs to tackle both sides of the obesity equation (ie. “When calories in … exceeds calories out” and “modifying both energy intake and energy expenditure”) but their solution will not change ‘calories in’ and does not have realistic prospect of effecting ‘calories out’.

EDIT: On the 9th May 2016 a piece by Nick Triggle was posted on BBC News which highlights the disparity alluded-to in the final section of this blog: “Some 58% of advertising spend is on confectionery and convenience food, compared to only 3% on fruit, vegetables and pasta” What Yoghurt Tells Us About The Obesity Fight retrieved 09/05/2016.

After an opportunity opened up in Charlie‘s workload we have finally managed to get our artisanal food generator coded and on a public-facing URL. We’d love you to give it a try. There is a previous post on this blog which tells you the story of why we think it demonstrates good persuasive thinking.

Late in 2015, we attended a Dare Sessions event with our friends The Foundry. The theme of the event was automation and David Atkinson from The Foundry referenced a wonderful bit of automation work where wine reviews were constructed using Markov Chains. This gives us some future direction perhaps in the logic although there is plenty to be getting on with as it is.

Finally, we’re proud to say that the associated Twitter account @shinyplums is gaining popularity although we’re not sure that everyone has worked out that it’s satirical. Which we rather like.

The only ‘disappointment’ personally was that Amanda Bacon’s food diary in US Elle shows us that no matter how ridiculous our strings might appear, the reality is much worse.