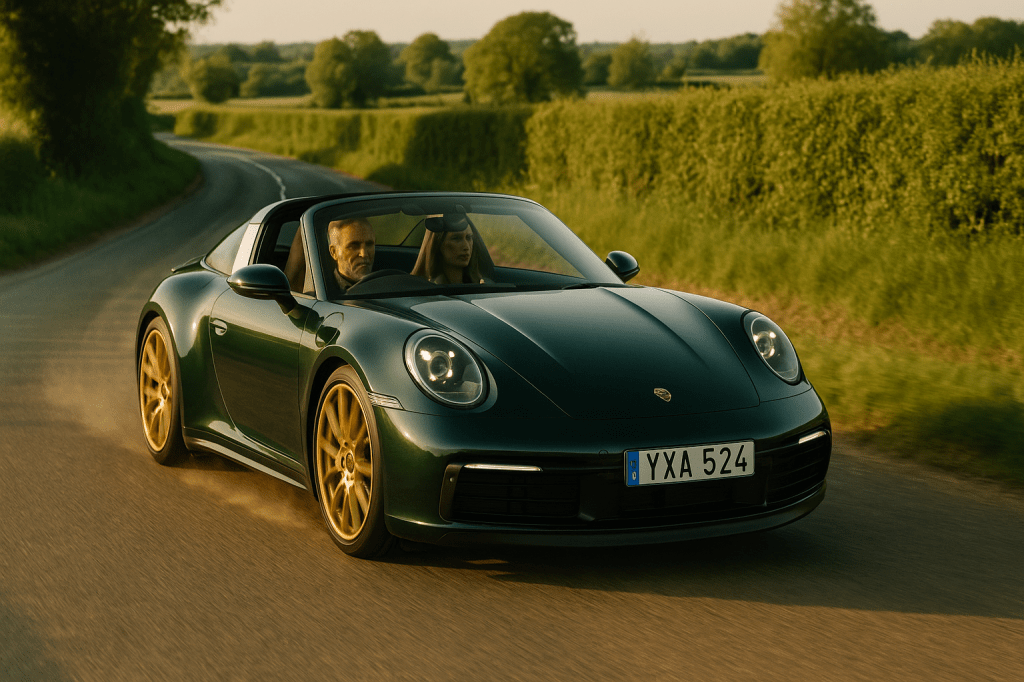

I recently got back from a couple of days away in Norfolk with a close friend who also loves his driving. We set out on a fantastic loop from Aylsham through Fakenham, Wells, and Cley – brilliant roads, good sightlines, measured effort, and our own playlists accompanying the sweat on the wheel and the red-hot calipers. It’s been seven years since we did something similar in Scotland on the North Coast 500, and while I’ve found a few roads round me in Surrey where I’ve had flashes of the same joy, doing it in perfect weather with a good friend is different. It’s memorable, visceral, and deeply satisfying.

Aside: The Horkey Kitchen at Bawdeswell is a worth stopping off point.

That trip reminded me what modern driving risks forgetting: rhythm, concentration, the way a great road stretches you just enough to feel vividly, physically present. A truth utterly ignored by the automotive press, which seems fixated on a frictionless future. Autonomy. Electrification. Over-the-air updates. The car, once a machine, is now a platform. A node on a smart grid. Another screen to poke and personalise. And if the future is to be believed, it’ll be a contactless glide from A to B – your vehicle knowing where you’re going, what mood you’re in, and curating the ambient playlist accordingly. Comforting, perhaps. But is that the future we really want?

Because here’s what happens when you flatten a journey into data points and strip the human out. You lose the sweat, the skill, the subtle joy of being in tune. What the current automotive vision tends to forget is this: flow beats frictionless. Every time.

Driving at its best is not about arrival. It’s about engagement. If you’ve ever taken the long way home just because the road was dry, the light was low and the playlist was perfect, you’ll know exactly what I mean.

Let’s be fair: 95% of driving is perfunctory. School runs. Trips to the tip. Visiting family. Airport drop-offs. Just get me there, and do it efficiently. That’s what satnavs are for, and they’re brilliant at it.

But just as we crave a real meal after a week of cobbled-together dinners, we also need room for the drives that feel like something. That remind us we’re not just being carried – we’re in it. That’s what this is about: reserving space for the exceptional.

Because flow isn’t just a productivity state. It’s the embodied feeling of rightness. An experience that draws on physical skill, real-time interpretation, being attuned to your environment. Strip that away, and something vanishes.

You can bolt as many sensors to the bumper as you like – flow isn’t something a car detects. It’s something a driver feels. But here’s the thing: technology doesn’t have to kill flow. It can co-create it.

The current HMI (Human-Machine Interface) paradigm presents a false binary. Either the driver is in control, or the system is. But there’s a third, more human path: co-piloting. Not Microsoft Clippy with a steering wheel, but a system attuned to how you want to feel on this drive. A route with rhythm. Camber. Flow. Roads that reward precision and tempo. Effort that meets intent.

When ease becomes the only design goal, something essential gets lost. And we’ve already seen what that looks like: In one eerily prescient experiment, researchers gave households a free chauffeur for 60 hours a week1 – as if driverless tech had already arrived. Public transport use plummeted. Total miles driven rose by 60%. Among retirees, it more than doubled. Why? Because friction disappeared. People sent cars to pick up friends, ran errands just because they could, and stopped weighing up whether a trip was worth it.

When mobility becomes passive, we don’t do less. We just do less meaningfully. Journeys blur. Movement becomes background noise. The vehicle ceases to be a site of agency or expression – it’s just another box we sit in while life happens elsewhere.

And that’s before we reckon with de-skilling. Driving draws on real-time judgement and physical awareness most of us rarely use elsewhere. Spatial reasoning. Risk calibration. Micro-adjustment. Automate that, and we don’t just lose control. We lose fluency.

Despite this, the appetite for engaged driving hasn’t gone – it’s just become more selective. The very existence of niche markets for classic cars, track days, and driving experiences proves it. That’s why designing for joy matters even more.

But this sits awkwardly alongside a cultural drift towards a one-size-fits-all mobility model – where driving is seen as a problem to solve, not a pleasure to preserve. It’s become unfashionable in some circles to even admit you enjoy it. As if to love driving is to reveal something suspect. But not all movement is equal. The same road can be a chore or a joy. It depends who’s driving, and why.

This shift in perception also affects how we measure success. The metrics used to justify infrastructure (usually based on time saved) miss the point. The real value lies in access gained, experiences unlocked, the long way round.

As behavioural economists have shown, effort often creates meaning. In a world of ‘frictionless’ experiences, friction can signal intention, depth, care.

Technology and craft, when designed with that richer journey in mind, can support and amplify, rather than replace. Like a great chef or a sound designer, it should highlight what matters and let the rest recede.

Imagine:

- Edge AI that reads your rhythm.

- Haptics that sharpen attention without nagging.

- Context-aware routes that change with the light, and the sky.

This emphasis on the physical and the intentional becomes even more crucial because the more we strip away, the more we’ll crave moments that remind us we still exist – bodily, skilfully, viscerally.

Especially in a world where younger generations increasingly see driving as a chore, or opt out altogether, the ones who do drive will be those who want to. That makes the case for joy-built design even stronger.

Because let’s be honest: the real enemy of joy on the road isn’t speed limits or EV ranges or even other drivers. It’s waste. Wasted road. Wasted time. Wasted potential for a moment of synchronicity between human, machine, and landscape.

If the future of automotive is to feel like anything at all – if it’s to be more than a Netflix-enabled transportation pod – we need to stop designing for the eradication of friction, and start designing for the restoration of rhythm.

Not just arrival. But aliveness.

AI Disclosure: This piece was written with the assistance of AI, used as an editorial and thinking partner. All ideas, edits, and final phrasing are mine. Image creation was by AI, natch – ALT text included. Excerpt and tag lists were also optimised for best practice

- The study has its limitations of course. It took place in the US where driving is end-to-end whereas Europeans focus is on automation for the last-mile and the public transport is sufficiently better to expect more inertia in behaviour ↩︎