I ran for 340 consecutive days before injury called time.

Yesterday I didn’t run. When I started out on January 1st this year I knew that whatever happened I’d be writing this post at some point. I’d have a body of runs to reflect upon, I’d have things I’d learned, I’d have a new level of fitness, a Strava record and a few Instagrams to show. Of course, I’d hoped I’d be writing it on 1st January 2017, not 25 days earlier.

As a runner in the age of ‘the quantified self’ and, dare I say it in a society that encourages it, I have become as fixated as anyone on the outcome. We’re hard-wired to value completion, if we didn’t where would we be? The pyramids might lie unfinished, Mona Lisa unpainted, the Apollo rockets unfired. Dialling back the hyperbole, this very human evolutionary trait has exerted its powerful influence on my desire to run every single day.

There were many days when a run was the last thing I wanted to do. The obvious reasons abound; cold, dark, wet, tired, hungry. There were nights that I ran in spite of emotional and logistical stress: I ran when Jo thought I wasn’t, I ran when I should have been home sooner, I ran the night after my son came home from a trip to A&E while Jo put him to bed. I’m not proud of the subversion, the missed moments with family nor the inevitable upset over mixed priorities.

But I am proud of the process. As time wore on I began to feel that the effort of making time every single day to plan ahead, get kit in the right place and at least a two-mile route to run meant that I could demonstrate to the many many people who say “I haven’t got time” that you really do. You don’t need to run every day of course and that’s not the point, the point is that two miles are not a difficult proposition when you’re asking for just 20 minutes a day.

Switching from that outcome focus and returning to the process, I’d like to highlight a few of the things I learned and developed along the way. In the plan for 2016 were two marathons, Stockholm and York. Although Stockholm wasn’t until June it did guide my efforts in the first months of the year. I tried to supplement the daily commute runs with the odd mid-week longer run and a long slow run at the weekend. Commute runs were reasonably quick efforts with bags which quickly had an impact on my shorter faster runs. parkrun times were consistently lower than before and I found my slow long run pace had got quicker even though effort remained the same. My most consistent high volume weeks were through the spring. The old commute run to and from Tabernacle Street was straightforward and effective. Combined with my simple work ‘uniform’, the months just ticked by in a largely positive fashion. I was surprised that the niggles came and went without developing into anything. My long-standing patellar tendon issues eased and I just kept going. Weight dropped off, not by design but by simple nutritional deficit. More on that later. Stockholm was a great race, hugely enjoyable and one I’ll look back on fondly. I felt I could even have gone a little quicker but the summer was still young and York was on the horizon. I had some great runs over the summer. Three fast timed miles at the City mile and Arethusa miles, joining Martin and Liz Yelling for my first super long day down on the South West Coast Path (SWCP) and then, later in the season, more SWCP running with Jo.

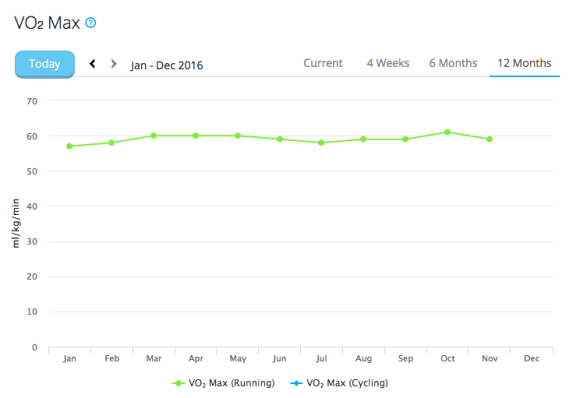

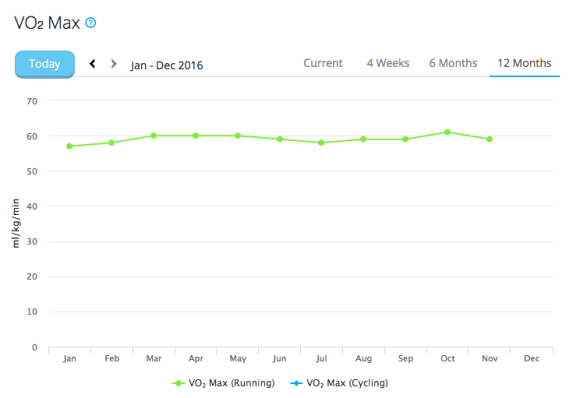

The hills, the mile speed and the strength work I did on those runs combined with some new routes around Surbiton had serious benefit. In fact, the need to find new routes really was a benefit. I found myself plotting by distance and exporting these to my watch, following unfamiliar roads and trails throughout Surrey and SW London. I got very familiar with the Thames Path all the way to Windsor or up to Battersea, and occasionally beyond. I doubt I’d have done this without some desire to break away from the monotony of the commute runs. By the late summer and autumn, I was sufficiently focussed on York, albeit with lower weekly totals than the spring training block. I remember my final dawn-start long training run through Epsom and Esher that finished with a 5k parkrun and topped off a massive week for me. I ran a race I was really proud of (a PB 3 12′ 50″) and came off the back of it with a 18:32 parkrun PB and a VO2 max estimated at 61 ml/kg/min in October.

A plot from Garmin’s estimated VO2 Max during my runstreak

Looking back I wonder whether that’s where it really ended. Although I felt fast and was running injury free I didn’t really have a target in mind for the final three months other than finish. 2 miles (3.22k) every day. As a consequence, I resigned myself to a commute run most nights and the weekly totals plummetted. Injuries typically occur after a change in training; a volume or intensity spike, a change of surface or other environments. In my case, the move to a new office location meant my run back to Waterloo was shorter, faster and downhill most of the way. It was also now entirely dark and involved notably more kerbs, junctions and slow-moving pedestrians. This meant I was juddering to a halt from speed a lot more than the old (still frustrating) route from Tabernacle Street. I was slamming down hard off the kerbs and putting shearing and twisting forces through my ankles more like a midfielder than a runner. Added to that (and hindsight bias is strong at this point) I ignored a low-level niggling plantar fascia problem for several months.

The net result was an angry Achilles after a long run along the towpath in trail shoes. I thought it was just some soreness due to the conditions and shoes but it didn’t ease and I didn’t give it enough attention with NSAIDs, ice and massage. I saw my daily commute as an easy run, unaware of the more unconventional impact it was having. It hurt to run that route yet I could manage a comfortable easy loop at home and do an ordinary slow parkrun. But on Monday night I ran back to the station and early on felt a stabbing pain unlike the usual irritation. I carried on but with 800m or so left to run I jarred it again and i knew I couldn’t bear weight on it, there and then I knew it was over.

Presumptively I’d booked Liam for the Tuesday evening and had hoped that i’d wake up that morning feeling that seeing him in the evening would mean he’d just be helping me to release some tension and I’d have managed a run in the day. But no. It just wasn’t an option, I had pain all day just walking and found myself wincing each time I climbed or descended stairs. The prognosis isn’t bad. Recovery should be straightforward with a decent regimen of slow and heavy resistance work after the acute inflammation has eased. Liam supports active recovery so I expect to be able to jog lightly soon enough and as I write this 48 hours later there isn’t pain walking. The biggest injury (apologies for the rather obvious cliche) is in my mind.

I’ve taken a lot from being part of and reading about Martin’s failed SWCP run earlier this year. The lengthy post-mortem on Marathon Talk and on his blog have helped put this kind of personal challenge in perspective. It will always smart that I fell short but writing this now and reflecting on what I taught myself over the period is fantastic.

- I’ve run more than ever – but I know I can do even higher weekly distances in future.

- You can run on rest days, as long as you run at markedly lower intensity, lower volume or both.

- Speed work has a huge benefit. Regular endurance work has a huge benefit. If you can work both into your schedule you will move beyond your ‘local maximum’.

- There are very few days and very few environments where you can’t get a run in. It requires prediction, planning and a tolerance for what constitutes a run.

- You don’t need a tonne of kit. I wore two-three pairs of shorts and the same number of technical shirts. I did burn through at least three pairs of Adidas adios boosts but I bought previous season models and used Vitality discounts to keep these purchases under £100 each time.

- Foul weather running is grim but nothing you experience in the non-mountainous UK is a reason not to run.

- It helps to have a wife who runs and running buggy. Tolerance from my son and empathy for my behaviour from Jo and our son was hugely beneficial.

- It helps having colleagues and an employer who support your lifestyle. Not being on-time, wearing running kit in the office, being a Strava Wanker can be irritating. Dare just let me be and, even occasionally, celebrated what I was doing.

So with my evenings a little calmer, my commute a little longer and my VO2 max a little lower, I can settle into a few weeks of planning what 2017 might hold. There’s precious little point sharing my present thinking here as it’s just as likely to be different tomorrow. There is the small matter of the British Indoor Rowing Champs on Saturday with my old University crew mates for which I have not prepared, not rowing a single stroke before the day. After that I know my motivations are in several directions: vanity to gain weight and muscle mass, strength and flexibility to protect against injury more, pleasure to enjoy running again at a variety of intensity, volume and environment and finally a few soft PBs that need some attention (as well as some hard ones too).

It was a long post, as much (more?) for me than for you, dear reader, but I hope valuable to some in various ways.

All the Strava data

My Smashrun visualisations showing trailing averages, intensities etc.