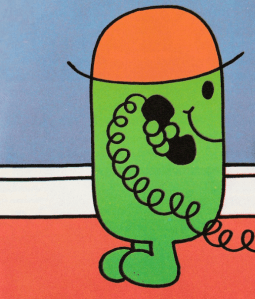

The other day, I was reading a children’s book with our daughter when I saw it: a corded telephone. Black, wall-mounted, with a dangling spiral wire. The sort of phone that last rang in anger sometime around the Blair years.

A few mornings later, it happened again, Baby Club on the BBC, all primary colours and soft clapping, and there, on the play mat , was a car. Not one she’d ever recognise. A boxy saloon. Straight-edged. Round headlights. The kind of thing you’d find idling outside a golf club in 1987.

What’s odd isn’t that these images exist, they’re charming, even lovingly drawn. It’s that they still feel like the default. Most phones today are glass bricks. Most cars look like they’ve been inflated rather than put together in a factory.

But when we illustrate for children, we reach back, not to what they know, but to what we remember. This isn’t a developmental crisis. Children don’t need realism to read meaning.

Jean Mandler’s research (thank you ‘Ai research team’) showed they use schematic categories, “car,” “dog,” “phone”, not photoreal recall.

Furthermore, Ellen Winner proved they can grasp symbolism early on (i.e. hey don’t need realism to understand things). So, no one’s confused. That’s not the point. The point is that these images persist, long after their referents have disappeared. The floppy disk still means save. A film reel still means video. A telephone still curls like a question mark.

We say it’s just design shorthand, but it isn’t. It’s something stickier.

These are the ghosts of our interfaces, icons of touchpoints no child will ever touch.

Gunther Kress‘ observations describe how meaning doesn’t update on command. It drags history behind it and changing the meaning of symbols requires overcoming an awful lot of cultural inertia. And children’s media, shaped entirely by adults, ends up as a kind of curated hauntology: a world that looks nothing like theirs, but everything like ours did, right around the time we were their age.

They swipe past rotary phones, expect Santa to come down a chimney no longer connected to a fireplace, draw little square cars with four doors and no raised suspension. It’s sentimental and not remotely sinister but it does mean they grow up consuming artefacts of use they’ll never need.

And maybe that’s fine. Maybe it’s like castles in fairy tales. But it’s hard not to feel the ache of it, that their books are filled with our objects, our past, our cultural residue.

Perhaps more concerningly, they’re not learning to navigate the world as it is. They’re learning to decode the leftovers of how we once did.

So I find myself wondering now what a picture book drawn from today would look like. Would the car even be recognisable? Would anyone bother sketching a glass rectangle phone? Or would the page just show a toddler, alone, swiping at the air, waiting for something to respond.

AI: This piece used AI to help me research the psychology references and summarise their observations. I used it for the tags, excerpt, and a little sub-editing. The ideas, references, and anecdotes were all mine.