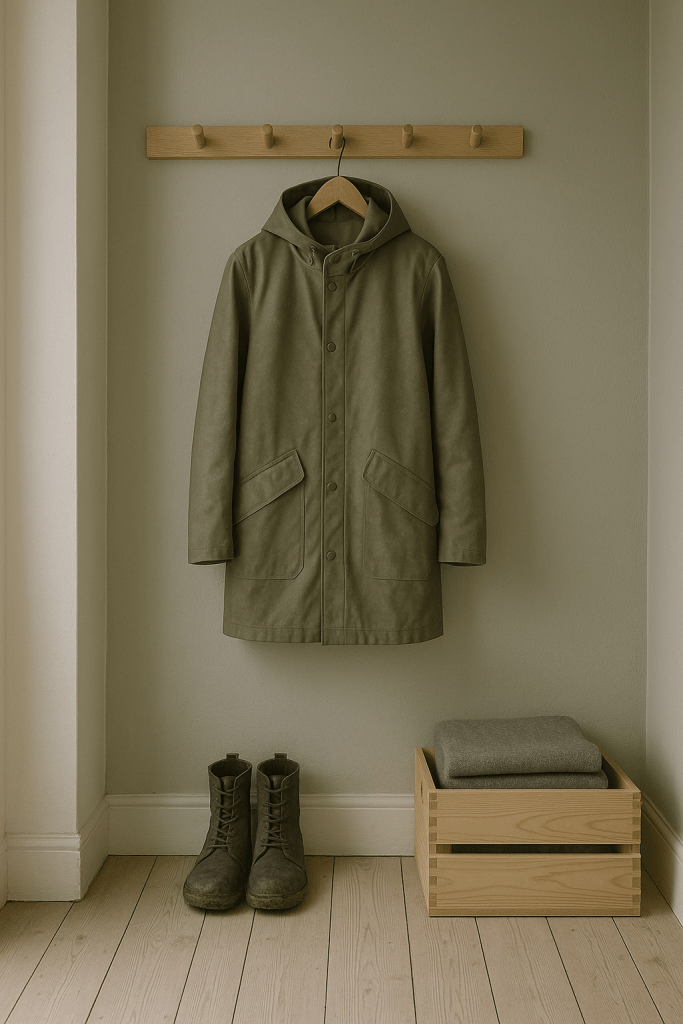

There’s a jacket hanging by the door in my house that I haven’t cleaned in two winters. A Stutterheim. Patina-stained cotton lining, scuffed hems, smells faintly of trains home. It’s not there for effect. It’s there because it does the job, and does it well. Keeps me dry, holds its own in a cold wind, and feels like continuity. Like something I’d pass on.

I think about that jacket sometimes when I work on digital products.

Because that jacket belongs in the doughnut. Not the jam-filled kind, the one drawn up by economist Kate Raworth. A model for living that rejects the old story of perpetual growth. (Aside: I came across Kate after listening to her talking with Wendell Berry on an old Start The Week. I’d gone on a recommendation from a friend to listen to Wendell Berry but it was Kate’s words which stood out).

In her diagram, the inner ring marks the essentials everyone should have access to: housing, education, dignity. The outer ring is the ecological ceiling: carbon, biodiversity, planetary boundaries. The goal is to stay in the middle. A safe and just space for humanity. Not too little. Not too much.

If that sounds like the Swedish concept of lagom, it is, except Raworth turns the cultural instinct into an economic framework. Lagom is what you feel in a table spread done right. The doughnut is how you design a city, or a system, to honour that logic at scale.

I like that the analogy might be in the Scandi larder: leftovers, carefully labelled. No waste, no lack. Just enough. The doughnut was already there, sitting quietly behind the knäckebröd.

And it maps cleanly onto UX.

The inner ring is what users genuinely need: clarity, trust, human-scale interaction. The outer ring is where the harm begins: deceptive patterns, compulsive loops, the kind of design that counts your seconds, not your needs. The good space, the space between, is where most digital products ought to live. Few do.

I’ve sat in rooms where product success was measured in taps and minutes. “More engagement,” someone would say, as the design team quietly recalibrated the interface to make it just sticky enough. I once worked on a platform where the proudest achievement was a spike in repeat logins. But when you zoomed out, those logins weren’t signs of confidence, they were symptoms of anxiety. People checking their accounts too often, not because the experience was smooth, but because the world wasn’t.

The real win would’ve been a design so clear, so calmly informative, so self-contained that users didn’t feel the need to check at all. But that wouldn’t have shown up on the dashboard. So we built noise instead. Goodhart’s Law anyone?

Doughnut thinking asks: what if we stopped designing for addiction and started designing for enough?

That principle runs through how I live. I’m not a minimalist, but I edit constantly. I favour things with integrity, materials that soften over time, ceramics that stack properly, garden tools that can be sharpened and passed on. When I write, I do so in iA Writer not because it’s clever, but because it clears the room. No distractions. Just text, gently weighted. A space with boundaries. A space that respects my focus. The writing comes better that way, less like performance, more like sorting the drawers in your head.

Same goes for the shelves at home. They hold only what earns its place. Books we’ve read. Things we actually use. Jackets that walk. Nothing there for the feed. Just our curated, persistent things.

Raworth talks about moving from extractive to regenerative economies. I think homes can be regenerative too, giving back emotionally, energetically, even ecologically, if you can. They absorb chaos. Offer rhythm. Ask less from you over time.

What does that actually look like?

There are just enough chairs for the family and the odd visitor. You can find a corkscrew without rummaging. There’s PIR lighting that flicks on as you walk from the landing to the bathroom at night. The house soaks up the mess. Fewer decisions when you’re tired. You can sit down without having to clear a pile of crap off the sofa. You can find your bloody keys.

It offers rhythm because your day moves more smoothly. And it asks less of you because it doesn’t make you work just to function.

My old boss used to moan that he couldn’t do a simple task at home because, to do that, he first had to find the tool. To find the tool, he had to get into the garage. He couldn’t get into the garage because the door was jammed. And on it went. That’s the opposite of regenerative. That’s a house that’s extracting energy from you just to stand still.

I wrote recently about the psychology of our stuff—the emotional residue it carries, the complexity it adds, the space it quietly swallows. The art of owning less isn’t about minimalism. It’s about clarity. About asking not ‘is this useful?’ but ‘is this mine to carry?’ That same lens applies here. Whether it’s a shelf, a digital feature, or a mental habit, we need to ask: is this giving something back? Or is it just squatting in the system?

And if that principle holds for homes, it can hold for digital spaces too. Interfaces, when well-designed, have the same potential, not just to serve, but to settle. To restore a little order. To give back time, attention, clarity. The question in both cases is not just what they contain – but how they behave when no one’s watching. Do they hold their shape under pressure? Or do they reveal they were only ever designed for the demo?

That’s what I try to bring into my UX work. Not scale for its own sake, but structure. Not novelty, but fidelity. In one recent project, we reduced a sprawling mass of order summary calculations by half. It had grown lopsided: multiple totals, stacked qualifiers, contradictory line logic. It looked thorough but made people pause. Double-check. Drop off.

We didn’t cut because someone asked us to. We cut because the excess wasn’t helping anyone. The business didn’t love it at first, there was concern we’d sacrificed transparency. But the users did. Completion held. Conversion held. No one missed the clutter.

You don’t need to call it Doughnut Economics. You don’t even need the diagram. Just ask: is this too much, or just enough? Is it serving someone, or keeping them circling?

I’m learning the same rules apply emotionally. The inner ring is what I need to function: rhythm, ritual, some quiet between the noisy pulses of family life. The outer ring is burnout, distraction, the endless need to ‘improve’. If I stay within those boundaries, wake early, behave deliberately, write when the coffee’s still hot – I do better work. I’m a steadier father. Less reactive. More intact.

We’ve built systems that confuse excess for success. But maybe the most humane thing we can do now is not build something. Or build something simpler. Or design the thing so well it doesn’t need us anymore.

Like the coat. You don’t notice it most days. But when the rain starts, you’re glad it’s there. And when you finally pass it on, it still fits someone else.

This piece was refined using AI. I used it to generate the image prompt, the tags, the excerpt, and to help sub-edit the copy while keeping my tone intact. The ideas, references, and rhythm are mine. The tools just cleared the room.